History of Earth

The history of Earth covers approximately 4.6 billion years (4,567,000,000 years), from Earth’s formation out of the solar nebula to the present. This article presents a broad overview, summarizing the leading, most current scientific theories.

Origin

The Earth formed as part of the birth of the Solar System: what eventually became the solar system initially existed as a large, rotating cloud of dust, rocks, and gas. It was composed of hydrogen and helium produced in the Big Bang, as well as heavier elements ejected by supernovas. Then, as one theory suggests, about 4.6 billion years ago a nearby star was destroyed in a supernova and the explosion sent a shock wave through the solar nebula, causing it to gain angular momentum. As the cloud began to accelerate its rotation, gravity and inertia flattened it into a protoplanetary disk oriented perpendicularly to its axis of rotation. Most of the mass concentrated in the middle and began to heat up, but small perturbations due to collisions and the angular momentum of other large debris created the means by which protoplanets began to form. The infall of material, increase in rotational speed and the crush of gravity created an enormous amount of kinetic heat at the center. Its inability to transfer that energy away through any other process at a rate capable of relieving the build-up resulted in the disk's center heating up. Ultimately, nuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium began, and eventually, after contraction, a T Tauri star ignited to create the Sun. Meanwhile, as gravity caused matter to condense around the previously perturbed objects outside of the new sun's gravity grasp, dust particles and the rest of the protoplanetary disk began separating into rings. Successively larger fragments collided with one another and became larger objects, ultimately destined to become protoplanets. These included one collection approximately 150 million kilometers from the center: Earth. The solar wind of the newly formed T Tauri star cleared out most of the material in the disk that had not already condensed into larger bodies.

The Hadean eon

The early Earth, during the very early Hadean eon, was very different from the world known today. There were no oceans and no oxygen in the atmosphere. It was bombarded by planetoids and other material left over from the formation of the solar system. This bombardment, combined with heat from radioactive breakdown, residual heat, and heat from the pressure of contraction, caused the planet at this stage to be fully molten. During the iron catastrophe heavier elements sank to the center while lighter ones rose to the surface producing the layered structure of the Earth and also setting up the formation of Earth's magnetic field. Earth's early atmosphere would have comprised surrounding material from the solar nebula, especially light gases such as hydrogen and helium, but the solar wind and Earth's own heat would have driven off this atmosphere.

This changed when Earth was about 40% its present radius, and gravitational attraction allowed the retention of an atmosphere which included water. Temperatures plummeted and the crust of the planet was accumulated on a solid surface, with areas melted by large impacts on the scale of decades to hundreds of years between impacts. Large impacts would have caused localized melting and partial differentiation, with some lighter elements on the surface or released to the moist atmosphere.

The surface cooled quickly, forming the solid crust within 150 million years; although new research suggests that the actual number is 100 million years based on the level of hafnium found in the geology at Jack Hills in Western Australia. From 4 to 3.8 billion years ago, Earth underwent a period of heavy asteroidal bombardment. Steam escaped from the crust while more gases were released by volcanoes, completing the second atmosphere. Additional water was imported by bolide collisions, probably from asteroids ejected from the outer asteroid belt under the influence of Jupiter's gravity. The planet cooled. Clouds formed. Rain gave rise to the oceans within 750 million years (3.8 billion years ago), but probably earlier. Recent evidence suggests the oceans may have begun forming by 4.2 billion years ago. The new atmosphere probably contained ammonia, methane, water vapor, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen, as well as smaller amounts of other gases. Any free oxygen would have been bound by hydrogen or minerals on the surface. Volcanic activity was intense and, without an ozone layer to hinder its entry, ultraviolet radiation flooded the surface.

Life

The details of the origin of life are unknown, though the broad principles have been established. Two schools of thought regarding the origin of life have been proposed. The first suggests that organic components may have arrived on Earth from space, while the other argues for terrestrial origins. The mechanisms by which life would initially arise are nevertheless held to be similar. If life arose on Earth, the timing of this event is highly speculative—perhaps it arose around 4 billion years ago. In the energetic chemistry of early Earth, a molecule (or even something else) gained the ability to make copies of itself–the replicator. The nature of this molecule is unknown, its function having long since been superseded by life’s current replicator, DNA. In making copies of itself, the replicator did not always perform accurately: some copies contained an “error.” If the change destroyed the copying ability of the molecule, there could be no more copies, and the line would “die out.” On the other hand, a few rare changes might make the molecule replicate faster or better: those “strains” would become more numerous and “successful.” As choice raw materials (“food”) became depleted, strains which could exploit different materials, or perhaps halt the progress of other strains and steal their resources, became more numerous.cator might have developed. Different replicators have been posited, including organic chemicals such as modern proteins, nucleic acids, phospholipids, crystals, or even quantum systems. There is currently no method of determining which of these models, if any, closely fits the origin of life on Earth. One of the older theories, and one which has been worked out in some detail, will serve as an example of how this might occur. The high energy from volcanoes, lightning, and ultraviolet radiation could help drive chemical reactions producing more complex molecules from simple compounds such as methane and ammonia. Among these were many of the relatively simple organic compounds that are the building blocks of life. As the amount of this “organic soup” increased, different molecules reacted with one another. Sometimes more complex molecules would result—perhaps clay provided a framework to collect and concentrate organic material. The presence of certain molecules could speed up a chemical reaction. All this continued for a very long time, with reactions occurring more or less at random, until by chance there arose a new molecule: the replicator. This had the bizarre property of promoting the chemical reactions which produced a copy of itself, and evolution began properly. Other theories posit a different replicator. In any case, DNA took over the function of the replicator at some point; all known life (with the exception of some viruses and prions) use DNA as their replicator, in an almost identical manner

Cells

Modern life has its replicating material packaged neatly inside a cellular membrane. It is easier to understand the origin of the cell membrane than the origin of the replicator, since the phospholipid molecules that make up a cell membrane will often form a bilayer spontaneously when placed in water. Under certain conditions, many such spheres can be formed (see “The bubble theory”). It is not known whether this process preceded or succeeded the origin of the replicator (or perhaps it was the replicator). The prevailing theory is that the replicator, perhaps RNA by this point (the RNA world hypothesis), along with its replicating apparatus and maybe other biomolecules, had already evolved. Initial protocells may have simply burst when they grew too large; the scattered contents may then have recolonized other “bubbles.” Proteins that stabilized the membrane, or that later assisted in an orderly division, would have promoted the proliferation of those cell lines. RNA is a likely candidate for an early replicator since it can both store genetic information and catalyze reactions. At some point DNA took over the genetic storage role from RNA, and proteins known as enzymes took over the catalysis role, leaving RNA to transfer information and modulate the process. There is increasing belief that these early cells may have evolved in association with underwater volcanic vents known as “black smokers”. or even hot, deep rocks. However, it is believed that out of this multiplicity of cells, or protocells, only one survived. Current evidence suggests that the last universal common ancestor lived during the early Archean eon, perhaps roughly 3.5 billion years ago or earlier.[20],[21] This “LUCA” cell is the ancestor of all cells and hence all life on Earth. It was probably a prokaryote, possessing a cell membrane and probably ribosomes, but lacking a nucleus or membrane-bound organelles such as mitochondria or chloroplasts. Like all modern cells, it used DNA as its genetic code, RNA for information transfer and protein synthesis, and enzymes to catalyze reactions. Some scientists believe that instead of a single organism being the last universal common ancestor, there were populations of organisms exchanging genes in lateral gene transfer.

Photosynthesis and oxygen

It is likely that the initial cells were all heterotrophs, using surrounding organic molecules (including those from other cells) as raw material and an energy source. As the food supply diminished, a new strategy evolved in some cells. Instead of relying on the diminishing amounts of free-existing organic molecules, these cells adopted sunlight as an energy source. Estimates vary, but by about 3 billion years ago, something similar to modern photosynthesis had probably developed. This made the sun’s energy available not only to autotrophs but also to the heterotrophs that consumed them. Photosynthesis used the plentiful carbon dioxide and water as raw materials and, with the energy of sunlight, produced energy-rich organic molecules (carbohydrates).

Moreover, oxygen was produced as a waste product of photosynthesis. At first it became bound up with limestone, iron, and other minerals. There is substantial proof of this in iron-oxide rich layers in geological strata that correspond with this time period. The oceans would have turned to a green color while oxygen was reacting with minerals. When the reactions stopped, oxygen could finally enter the atmosphere. Though each cell only produced a minute amount of oxygen, the combined metabolism of many cells over a vast period of time transformed Earth’s atmosphere to its current state. Among the oldest examples of oxygen-producing lifeforms are fossil Stromatolites.

This, then, is Earth’s third atmosphere. Some of the oxygen was stimulated by incoming ultraviolet radiation to form ozone, which collected in a layer near the upper part of the atmosphere. The ozone layer absorbed, and still absorbs, a significant amount of the ultraviolet radiation that once had passed through the atmosphere. It allowed cells to colonize the surface of the ocean and ultimately the land; without the ozone layer, ultraviolet radiation bombarding the surface would have caused unsustainable levels of mutation in exposed cells. Besides making large amounts of energy available to life-forms and blocking ultraviolet radiation, the effects of photosynthesis had a third, major, and world-changing impact. Oxygen was toxic; probably much life on Earth died out as its levels rose (the “Oxygen Catastrophe”).Resistant forms survived and thrived, and some developed the ability to use oxygen to enhance their metabolism and derive more energy from the same food.

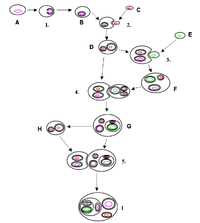

Endosymbiosis and the three domains of life

Modern taxonomy classifies life into three domains. The time of the origin of these domains are speculative. The Bacteria domain probably first split off from the other forms of life (sometimes called Neomura), but this supposition is controversial. Soon after this, by 2 billion years ago, the Neomura split into the Archaea and the Eukarya. Eukaryotic cells (Eukarya) are larger and more complex than prokaryotic cells (Bacteria and Archaea), and the origin of that complexity is only now coming to light. Around this time period a bacterial cell related to today’s Rickettsia entered a larger prokaryotic cell. Perhaps the large cell attempted to ingest the smaller one but failed (maybe due to the evolution of prey defenses). Perhaps the smaller cell attempted to parasitize the larger one. In any case, the smaller cell survived inside the larger cell. Using oxygen, it was able to metabolize the larger cell’s waste products and derive more energy. Some of this surplus energy was returned to the host. The smaller cell replicated inside the larger one, and soon a stable symbiotic relationship developed. Over time the host cell acquired some of the genes of the smaller cells, and the two kinds became dependent on each other: the larger cell could not survive without the energy produced by the smaller ones, and these in turn could not survive without the raw materials provided by the larger cell. Symbiosis developed between the larger cell and the population of smaller cells inside it to the extent that they are considered to have become a single organism, the smaller cells being classified as organelles called mitochondria. A similar event took place with photosynthetic cyano bacteria entering larger heterotrophic cells and becoming chloroplasts.Probably as a result of these changes, a line of cells capable of photosynthesis split off from the other eukaryotes some time before one billion years ago. There were probably several such inclusion events, as the figure at left suggests. Besides the well-established endosymbiotic theory of the cellular origin of mitochondria and chloroplasts, it has been suggested that cells gave rise to peroxisomes, spirochetes gave rise to cilia and flagella, and that perhaps a DNA virus gave rise to the cell nucleus, though none of these theories are generally accepted. During this period, the supercontinent Columbia is believed to have existed, probably from around 1.8 to 1.5 billion years ago; it is the oldest hypothesized supercontinent.

Multicellularity

Archaeans, bacteria, and eukaryotes continued to diversify and to become more sophisticated and better adapted to their environments. Each domain repeatedly split into multiple lineages, although little is known about the history of the archaea and bacteria. Around 1.1 billion years ago, the supercontinent Rodinia was assembling. The plant, animal, and fungi lines had all split, though they still existed as solitary cells. Some of these lived in colonies, and gradually some division of labor began to take place; for instance, cells on the periphery might have started to assume different roles from those in the interior. Although the division between a colony with specialized cells and a multicellular organism is not always clear, around 1 billion years ago, the first multicellular plants emerged, probably green algae. Possibly by around 900 million years ago, true multicellularity had also evolved in animals. At first it probably somewhat resembled that of today’s sponges, where all cells were totipotent and a disrupted organism could reassemble itself. As the division of labor became more complete in all lines of multicellular organisms, cells became more specialized and more dependent on each other; isolated cells would die. Many scientists believe that a very severe ice age began around 770 million years ago, so severe that the surface of all the oceans completely froze (Snowball Earth). Eventually, after 20 million years, enough carbon dioxide escaped through volcanic outgassing that the resulting greenhouse effect raised global temperatures. By around the same time, 750 million years ago, Rodinia began to break up.

No comments:

Post a Comment